As Washington state opens near-normally, we’ll see how well it can heal its wounds from the pandemic. There is the same uncertainty on the coast of America in the cities that were the business leaders before the pandemic.

One thing is already becoming clear, however: the pandemic is not going to save the heartland by rocking loose businesses and highly skilled workers from superstar cities like Seattle in favor of Cincinnati, St. Louis and other places left out of the “winning intake” all ” Urbanism.

Even the Brookings Institution, among the critics of “excessive concentration” of assets, has just thrown in the towel.

Brookings researchers, led by Mark Muro, found that estimated coastal relocations were to “secondary technology centers” – Austin, Texas; Denver; North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park – not ailing Dayton, Ohio.

In addition, the numbers do not support the narrative that the “COVID-19 pandemic has created a huge pool of freelance workers who are quickly leaving the major technology centers on the coast and heading to the heartland, where they will boost the domestic economy.”

For example, out of a total of 700,000 moves from the Bay Area in 2020, only 12,000 address changes were submitted for 19 “classic heartland states”.

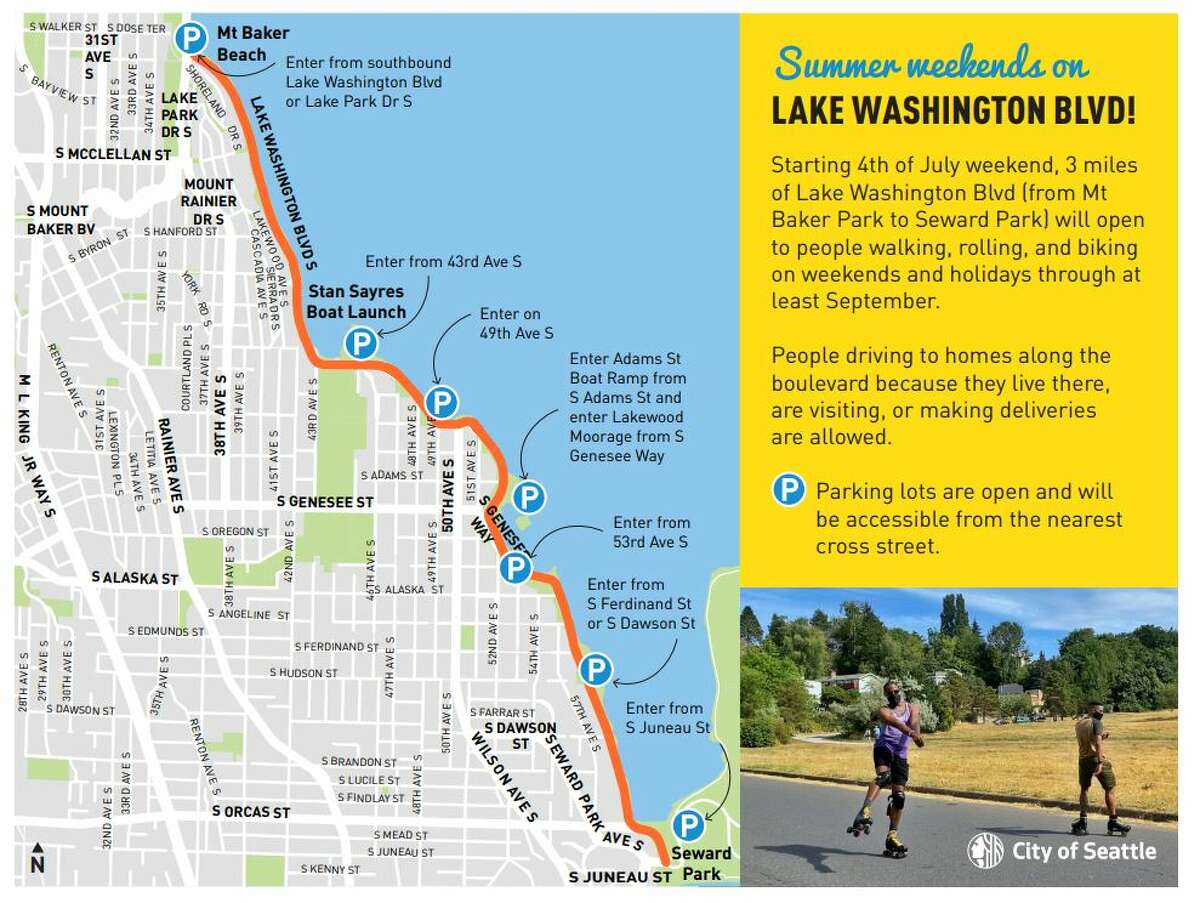

Data from the postal service and real estate company CBRE showed 479,785 moves from metropolitan Seattle last year. But only 28,192 went to mountain or heartland states. Seven Superstar metros recorded a total of almost 4.7 million outbound trains. Yet fewer than 198,000 went to mountain or heartland states.

The Brookings Report concludes: “This suggests that despite all the discussions about new work patterns and potential relocations, millions of professional workers will find it less and less complete in the years to come as remote working reaches a new level which will be higher than the pre-pandemic norm but lower than now.

“All of this means that most inland cities shouldn’t hold their breath for quick, migration-related turns generated by the arrival of new technical or professional workers from the coasts.”

Of course, we don’t know what the world will be like after the pandemic.

Some doubled the forecast later this year.

Derek Thompson of Atlantic Magazine wrote under the headline “Superstar Cities Are in Trouble” earlier this year, arguing that remote working would mark a new industrial revolution that would bring high-performance metros into decline.

He wrote, however, “Superstar pain could be America’s win – not only because lower housing costs in expensive cities make room for middle-class migrants, but also because the coastal diaspora will spur growth elsewhere.”

The data does not support this.

As my colleague Gene Balk reported, Seattle was the fastest growing city in the 2020 pandemic year.

The revenge of the heartland always had the element of a moral game. As if the superstar cities had caused the problems elsewhere. And now they would reap the whirlwind. But so far it’s hardly child’s play. The gains in places like Austin could have happened without the pandemic. We will never know.

In reality, industries have always concentrated, leaving winners and losers behind.

Chicago became the country’s railroad capital in the 19th century and still is today. Pittsburgh square steel. The burgeoning automotive industry grew from a dozen emerging centers to focus in Detroit. New York has cornered banking and finance.

The oil industry was centered in Houston, which defeated Tulsa, Oklahoma for the crown. Before Puget Sound became a world-class aerospace hub, Southern California was home to a huge aviation cluster.

In all of these cases, geography, innovation, boosterism, and luck played a huge role. Likewise, the exponential growth of these key industries after these older “superstars” became established.

But these examples also differed from today’s technology economy.

For one thing, the sectors often created widespread wealth well beyond their central core.

The auto industry, for example, built rallies across the country, eventually with hundreds of thousands of well-paid union jobs. The great inventor Charles Kettering founded Dayton Engineering Laboratories Co. to serve industry. It became Delco from General Motors. As recently as the 1980s, Dayton had the second largest number of GM employees in the world (today it has practically none).

Before lax antitrust enforcement, cities of all sizes had their local banks, department stores, railroad operations, and many hosted airline hubs (Dayton was a Piedmont Airlines hub) and large corporate headquarters (Dayton was home to the National Cash Register, later NCR, and Metpapier, both pulled away).

Now these economic crown jewels have long since disappeared from most inland cities.

This was due to bad luck, technological change and corporate betrayal, but also bad politics and not just the effects of the cartel or even trade on production. Some of the wounds were self inflicted. No wonder most of the 240+ places competing for Amazon HQ2 never stood a chance.

Much of the heartland appreciated tax cuts, which hampered education funding and investment in forward-looking projects. For years, the state of North Carolina has built the research triangle anchored by three major universities. Ohio did not succeed.

Today, when big tech is spreading its wings in places where there isn’t enough talent, universities, quality of life, and tolerance, it means low-end operations like data centers, call centers, and Amazon warehouses. All of them are considered great economic gains in “loser” locations, but they are no match for the widespread benefits of legacy industries.

So far, remote work and migration have not solved this challenge. But it is easier to envision a magical solution to the pandemic than it is to dig hard to rebuild the heartland.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/cmg/BPEI2QQ76SHPPOW6X6A6WHEGX4.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/cmg/GLQND2AXQQO2G4O6Q7SICYRJ4A.jpg)